Okay, so it’s the first day of Stromness Shopping Week and it was bound to be a beautiful day. By the evening I was ready for a breath of fresh air after being stuck in the gallery all day for the sale of one sodding card! £2.50 is not going to allow retirement any time soon. . . .

The weather was still very pleasant after dinner so I loaded the scope and tackle into the car and made for Yesnaby. Lugging the Nikon and the Velbon 7000 video tripod a mile and a half with satchel of art gear and sketchbook was well worth it as I a dark phase skua rises over the ridge to investigate me. I meander across to my favourite rock (a la Shirley Valentine), place my binoculars on the ground and, as I swing the scope of my shoulders there’s a ‘crack!’ – the scope’s weight has snapped the holding screw off the tripod quick-release plate – oh super! I know it’s my own fault for being an idle sod and carrying the scope attached to the tripod, but the realisation only serves to darken my mood. The birds are too far away for binoculars – drawing through, at any rate, but I have a quick scan of the scene and locate a pale-headed skua. I’m pretty sure what it is but I have to get the scope hand-held onto the bird – a fully fledged arctic skua youngster! Now let’s no longer mince words about this bird – if arctic skuas were the commonest bird on the planet they would still grace any orni-porno site, as it is they are looking down the barrel of permanent oblivion from these isles, which makes this sight every so slightly welcome.

But the scope’s knackered. I try to bind the thing to the tripod with the strap which is fairly successful until; I realise that in doing so I’ve also fastened the barrel focus tightly too – smashing! Off it comes and I realise there’s no way to make it sit. But, by balancing the scope on the tripod head and moving it ever so carefully I can peer through the eyepiece and at my baby – gorgeous! I make a quick drawing in tone and just as I have got the hang of using this delicately balanced rig, a fecking dog-walker comes over the brow and straight through the territory. Fecking w@nker – but my birds are immediately at him and his mutt and I barely contain a laugh as this burly lad screams ‘fuck-off, fuck-off’ whilst waving his arms about at the dive-bombing skuas. Tit!

But it does give me the chance to see the chick can fly; albeit not with the sleek and graceful lines and curves s/he will (hopefully) achieve in the fullness of time. However it drops down behind the ridge and out of view. I’m just about to pack in when I notice one of the parents nearby. Again using the balancing act I train the scope and make a couple of drawings when from nowhere, the fog comes rolling over the hill obscuring just about everything. Ah - the joys of a warm day at the coast.

Then the chick is there again. And it’s doing something I’ve never seen – plucking at vegetation and eating it. Most curious and something I need to read up on. It’s hunched and shuffling gait recall its close relatives the gulls and it begs from its parent similarly; tapping on the bill in expectation. Then everything’s gone – the fog is total. I’m left with a trudge back to the car, dripping sketchbook and ruined tripod with barely a drawing in the book. But absolutely elated!

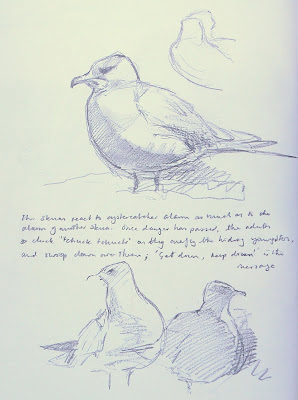

The sketches show a dark-phase arctic skua and then the same bird observed through the thickening fog, having relocated slightly. The studio piece is a composition using the fieldwork of the dark-phase/light-phase skua pair.

The following day I was determined to make amends for the debacle with the scope and, having replaced the quick-release plate, transported the scope and tripod separately. Entering the skua territory today was like being on a different planet; gone had all the gloom and mood of the previous evening (enchanting though that was), to be replaced by bright, warming sunlight and something I rarely have to contend with in Orkney (this year at least) – heat haze!

Fortunately my birds are growing accustomed to my hunched shuffling through their space and, as soon as I flop down on ‘the rock’ they seem to settle; the dark bird coming to rest not 30 metres from me. I intend to make a few investigative drawings, but my eye and pencil seem content to enjoy the one pose this bird has settled into and soon I have made a colour study describing the immediate scene.

Scanning the moor for alternative viewpoints I chance upon a youngster, then another; again one bird remains fairly motionless and allows involved study for 20 minutes or so. The light breeze occasionally rearranges the bird’s plumes and it flicks away the midges from its face.

A yowl of anger makes me turn and one of the neighbouring skuas takes off after a great black-back which has taken the wrong course. It sees the large gull off and helter-skelters back to its resting place among the sedges, calluna and cross-leaved heath. Then I see the cause of its worry; another fledgling – three in total in this small area. This is excellent news considering the skuas’ main provider, the arctic tern, has had such a terrible season and very few remain to be parasitized. I watch the adult and the youngster for the next half hour, all the while scribbling in my sketchbook.

The sketches are of the adults and youngsters: